The European Space Organization's (ESA) Aeolus space apparatus is planned to reappear Earth's climate tonight, covering a four-day circle bringing down crusade that could pioneer another path for satellite administrators.

"What we're doing is quite novel. "In the history of spaceflight, you don't really find really examples of this," said Holger Krag, head of the ESA's Space Debris Office, at a press briefing on July 19. This is the initial opportunity as far as anyone is concerned [that] we have done a helped reemergence like this."

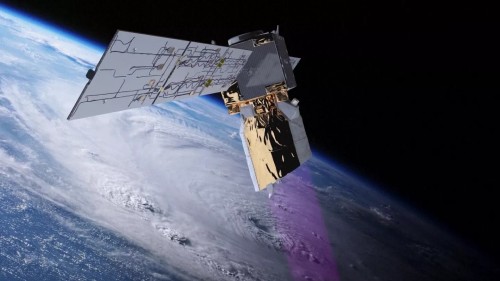

Aeolus was a trailblazer in life too. The 1,360-kilogram, 3,000-pound satellite was launched in August 2018 to observe Earth's winds in detail, something that had never been done before from space.

The space apparatus' information have assisted scientists with further developing their environment models and weather conditions estimates, ESA authorities have said. Additionally, the mission team discovered more of this data than anticipated: Aeolus functioned for nearly 4.5 years, which is approximately 18 months more than its planned scientific lifespan.

However, the spacecraft eventually started to run out of fuel. As opposed to allow Earth's climate to drag Aeolus down in a tumultuous design, similar to the standard for circling satellites, mission colleagues chose to play a more dynamic job in the rocket's death. They were in charge of the de-orbit campaign, which aims to ensure that Aeolus explodes over a clear stretch of the Atlantic Ocean and does not pose a threat to people or buildings on the ground.

That danger, however little, is genuine at whatever point a satellite falls uncontrolled to Earth: By and large, around 20% of a rocket's mass endures the red hot excursion through the environment and hits solid land (or, all the more generally, sea waters). Additionally, a lot of things up there are just waiting to be taken down.

"There are currently 10,000 spacecraft in space, 2,000 of which are inoperable. "We are talking about approximately 11,000 tons in terms of mass," Krag stated at the press conference on July 19.

He added that large objects reenter our atmosphere approximately once every week and that approximately 100 tons of human-made space junk lands on Earth annually.

Directed reemergences, which are normally performed by rocket stages after orbital send-offs, could assist with leaving a mark on this space-garbage issue. In this regard, the Aeolus team hopes to be an example.

Aeolus' reemergence crusade "starts a recent fad for safe shuttle tasks and feasible spaceflight, for both future missions and those generally in circle," ESA's Rosa Jesse wrote in a blog entry last month.

From an altitude of around 200 miles (320 kilometers), Aeolus studied Earth's winds. On June 19, the spacecraft began descending from this orbit, and five weeks later, the mission team began accelerating the process.

On Monday (July 24), Aeolus performed two motor consumes that endured a sum of 37.5 minutes and brought down its elevation by around 19 miles (30 km), to 155 miles (250 km). Four planned orbit-lowering maneuvers kicked off the campaign on Thursday (July 27).

According to ESA officials, a final maneuver is scheduled for today, with reentry anticipated approximately five hours later. However, at this time, it is too early to know when, where, or which regions of Earth might be able to witness Aeolus's blazing death dive. We'll simply need to look out for refreshes from ESA and the Aeolus group.

Aeolus' reentry may end up being at least partially uncontrolled and the assisted reentry may not go entirely according to plan. Yet, even all things considered, the ongoing effort would in any case have been worth the work, ESA authorities said.

"Effective or not, the endeavor makes ready for the protected return of dynamic satellites that were never intended for controlled reemergence," the office's Peter Bickerton wrote in a July 19 blog entry.